Washington tribal members encourage resistance against a North Dakota fossil-fuel project as a similar threat to developments they have opposed on their own ancestral lands.

They came by plane, bus and car, bringing food, songs and their finest regalia.

Tribes from across Washington and the Northwest have journeyed to remote Cannon Ball, N.D., to join the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in a peaceful occupation of ancestral lands where the tribe seeks an injunction to stop construction of an oil pipeline until its waters and cultural resources are protected.

At least eight tribes from Washington state — some have been through or are still engaged in similar battles of their own to block fossil-fuel projects on their own ancestral lands — have traveled to join the occupation. They are Yakama Nation, Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, Lummi Nation, Puyallup Tribe, Nisqually Indian Tribe, Suquamish Tribe, Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and Hoh Tribe.

More than 1,500 people from 150 tribes and their supporters from around the country have gathered at the confluence of the Cannonball and Missouri rivers, staging a nonviolent protest at what they call a spirit camp.

Native Americans from reservations hundreds of miles around have joined the growing protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline, causing the company to temporarily halt construction.

The Standing Rock Sioux have sued federal regulators for approving the pipeline, which will take crude oil from the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota to Illinois and cross the Missouri River just upstream of the reservation. The pipeline will pass through Iowa, Illinois, North Dakota and South Dakota.

The tribe argues that the pipeline would impact drinking water and sacred sites on its 2.3-million-acre reservation straddling the North Dakota-South Dakota border, harming thousands of residents on the reservation, and the millions of people who rely on clean drinking water downstream.

The tribe seeks an injunction from a federal judge — a ruling on which could come as soon as early September — to block further construction.

Most recently in the Northwest, the Lummi Nation defeated the proposed Pacific Gateway bulk terminal on its ancestral village site and burial grounds at Cherry Point in Whatcom County after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers denied permits for the project on the basis of its threat to treaty-protected fishing rights.

“We have seen the success our friends from Washington state have had in their battles to protect treaty rights against the transport of fossil fuels,” David Archambault II, chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, said in a prepared statement this week. “Their support is crucial in the protection of land, water and cultural resources as well as all of our sovereign rights … words can’t express how thankful we are.”

In traditional white buckskin regalia, and standing with a heap of fresh, fragrant cedar from Washington, JoDe Goudy, chairman of the Yakama Nation, in a welcome ceremony at the camp Tuesday said: “We, along with people of all walks of life, are observing a peaceful and prayerful gathering to move an entire country. … One voice, one heart, and one spirit to speak for those things that cannot speak for themselves.”

Tim Ballew II, chairman of the Lummi Indian Business Council, said in a phone interview from the camp that for his people, the protest is an opportunity to join forces in a common cause felt not only by Indian people but all people concerned for the well-being of the Earth.

“We hope to show a sign of solidarity for their efforts, to protect their sacred sites,” Ballew said of the Standing Rock Sioux.

He noted that support from other tribes and the broader community helped the Lummi succeed in their own efforts to protect their ancestral village site. “We couldn’t have come as far as we did without the help and support from our neighboring native nations, and all the support from throughout Indian Country. We thought it would be good to come out and pay the same respect.”

The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues is calling on the U.S. government to allow the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe to have a say regarding a $3.8 billion oil pipeline that it says could disturb sacred sites and impact drinking water for 8,000 tribal members.

In a statement issued Wednesday, the forum’s chairman, Alvaro Pop Ac, called for a “fair, independent, impartial, open and transparent process to resolve this serious issue and to avoid escalation into violence and further human rights abuses.”

The forum provides U.N. representation to indigenous people around the globe.

Seattle Mayor Ed Murray wrote Chairman Archambault on Aug. 26 “on behalf of the City of Seattle to express our solidarity in opposition to the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline across your territory.”

Lummi carvers also arrived at the camp this week with a totem pole, part of a journey undertaken by Lummi tribal members and supporters across Indian lands to protest fossil-fuel transport projects. Photos and videos of the journey are posted regularly on Facebook.

Their journey began Aug. 23, as the House of Tears Carvers of the Lummi Nation began a 5,000-mile trip across the Western United States and Canada with a 22-foot totem pole strapped in a pickup truck. The journey is intended to bring attention to proposed fossil-fuel terminals, oil trains, coal trains and oil pipelines, and to the tribes and local communities in their paths. The journey, including the arrival of the totem pole in the spirit camp, is chronicled online on the project’s website.

At the camp Tuesday, Brian Cladoosby, chairman of the Swinomish Tribe and president of the National Congress of American Indians, said in a prepared statement: “The clean water, salmon, buffalo, roots and berries, all that make up the places that First People have inhabited since time immemorial, bind tribes together.

“We are a place-based society. We live where our ancestors are buried. Our culture, laws and values are tied to all that surrounds us, the place where our children’s future will be for years to come. We cannot ruin where our ancestors are buried, and where our children will call home.”

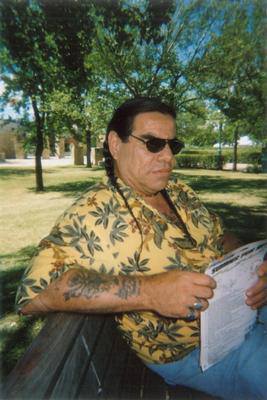

Stories abound about the Besieged Standing Rock Sioux of North Dakota, their struggle against the Dakota Access Pile Line (DAPL) or ‘Black Snake’ and endless western media prevarications. But while on assignment at the Oceti Sakowin Camp I also found another story. Granted, it was unexpected but it was also hard to ignore for it brought me back to the very essence of my core beliefs. In a way this became my personal pilgrimage.

Stories abound about the Besieged Standing Rock Sioux of North Dakota, their struggle against the Dakota Access Pile Line (DAPL) or ‘Black Snake’ and endless western media prevarications. But while on assignment at the Oceti Sakowin Camp I also found another story. Granted, it was unexpected but it was also hard to ignore for it brought me back to the very essence of my core beliefs. In a way this became my personal pilgrimage. and mental health facilities under construction within this sprawling encampment along the Cannon Ball River. I happened onto a yurt building class and was spell bound by this unique structure and it’s simplicity in assembly. But alas I resigned myself to my cousins dilapidated tent that survived a savage wind storm in a previous run to the rez. Some rope, Duct Tape and we were good to go.

and mental health facilities under construction within this sprawling encampment along the Cannon Ball River. I happened onto a yurt building class and was spell bound by this unique structure and it’s simplicity in assembly. But alas I resigned myself to my cousins dilapidated tent that survived a savage wind storm in a previous run to the rez. Some rope, Duct Tape and we were good to go.